by Albert J. Klumpp

Despite the current level of political turmoil throughout our country, last Tuesday’s election concluded one of the quietest judicial retention cycles on record. Nationally there were 692 state court judges seeking noncompetitive retention in eighteen different states. Pending some unreported results in Kansas and Indiana, 689 of the judges appear to have been retained. The lone exceptions were in Maricopa County, Arizona, where three trial court judges with less-than-perfect marks from the state’s judicial performance commission were on the verge of defeat, albeit with many thousands of ballots still to count.

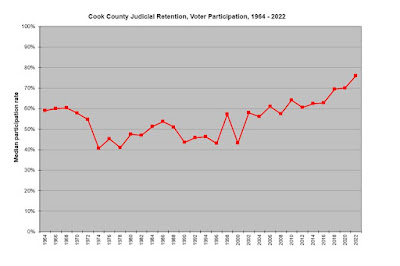

Here in Cook County, the voting indicated that the surge in interest in the retention part of the ballot that began in 2018 and grew in 2020 is starting to fade. This is not at all unexpected. The same happened during the Operation Greylord elections of the 1980s, and has happened in other jurisdictions as well. But while the post-Greylord voting was largely the same as the pre-Greylord voting, in this instance future retention elections are likely to settle into a somewhat different normal compared to the past.

Ballots are still being counted in both city and suburbs, but the retention numbers are complete enough to allow for a sufficient examination of the results:

- The reported voter turnout of 41% is the lowest for any November election since the adoption of judicial retention in 1964. Conversely, the median participation rate for the retention judges on the ballot was 76%, the highest level ever. Since it typically is the most regular and dedicated voters who complete the retention part of the ballot, the two figures in combination is not a surprise.

- The baseline approval rate for the 61 judges on the retention ballot, controlling for all positive and negative variables, was a historically typical 75.3 percent. This is exactly the same figure as in 2020 and just below the 75.4 percent level in 2018. (There in fact were 62 judges listed on the ballot, but unfortunately both the city and county election agencies did not report vote totals for the retiring Daniel Pierce.)

- Among the bar association ratings, the Illinois State Bar Association’s were by far the most influential at roughly eight percent of the vote, compared to roughly five percent for all of the other bars combined. In recent years the ISBA ratings have been reported more frequently by suburban media, so their growing influence is to be expected, and in fact was measured as growing in 2018 and 2020. However, in this election they were predominant among the bar groups even in the city. The eight percent figure may be a bit of an overstatement, due to the small overall number of negative ratings by the bars and the consequent difficulty in estimating their impact, but the trend is undeniable.

- The two social media guides from progressive activists that were detectable in the 2018 and 2020 voting were once again detectable here. The “Girl I Guess” guide was used by roughly 4.8 percent of the voters, while the “Cheat Sheet” guide circulated by the Chicago Votes group was used by roughly 1.6 percent. As expected, both were much more influential in the city than in the suburbs.

- Unlike the primaries, where name cues are highly influential and often determinative, name cues are of little significance in retention voting and were not a major influence here. Female judges did 1.8 percent better than males, and among the three most important race/ethnicity categories (Irish, Black, Hispanic), none was worth more than 1 percent.

- Overall roughly 200,000 voters made use of information from one of the above-named information sources to cast a mixture of yes and no votes. This is double the historically typical figure of 100,000, but only a fraction of the 400,000 in 2018 and the 520,000 in 2020. However, while the number is smaller than in the two previous elections, it occurred with no help whatsoever from either of the major metropolitan newspapers, The Sun-Times and Tribune both not only declined to offer any retention recommendations of their own, but did not even report any of the bar association ratings for informational purposes.

In 1887, 1921, 1953, 1984 and again in 2020 the local political powers-that-be suffered headline-generating embarrassments in judicial elections, because they forgot the lessons of the past and were repudiated by the electorate for trying to overly influence the process of judicial selection. It’s a remarkably cyclical pattern that repeats every thirty-something years, and proves the old adage of those who forget history being doomed to repeat it. This mailer may well be evidence of another cycle coming to a close.

Looking forward, if the Sun-Times and Tribune, which were significant drivers of retention votes in the past, continue to shun the retention candidates in the future, then future elections will continue to see the combination of the internet, social media and smartphones play the primary role in retention voting as they apparently did here. The mixture of information-based votes will be more political and less profession-oriented — especially considering that the bar community shows no interest in strategies to increase the use of its ratings, and seems oddly accepting of its lessening influence. This will likely occur regardless of the choices made by the county Democratic party.

When the results are official the ward and township numbers are final, I’ll share some detail from the analysis at that level. For now I’ll just add the usual fine print about how the figures cited above are statistical estimates with margins of error, but that on the whole they “fit” the retention results very well and describe the voting patterns accurately.

2 comments:

I would hardly call it an "embarrassment" or "repudiation" for the Democratic Party to successfully remove one judge and then come remarkably close to removing another. The real embarassment was the pyrrhic victory for the politically motivated critics of this sincere effort to reform our judicial system. They won the battle and lost the war. Most notably Lori Lightfoot. Her support for Judge Toomin out of sheer spite for the Democratic Party may well be remembered as her Waterloo.

Only about three percent of the 2020 retention vote was the direct result of the county party’s recommendations. And in 53 of the 80 wards and townships the party’s influence was statistically indistinguishable from zero. This was even after the extraordinary step of bringing in at least three popular U.S. Congress members to publicly criticize a county judge.

Fair enough, the party may have indirectly influenced some of the other information providers who had their own independent impacts. But it also triggered a backlash the likes of which has rarely been seen in more than 160 years of judicial elections in this county. Characterizing it all as anything remotely resembling a success, the evidence simply doesn't support that.

Post a Comment